“What drew you here?” asked the friendly woman at the desk at the Beothuk Interpretation Centre when we arrived at opening time that morning in June.

“A book,” I said.

“Some people come here after reading Michael Crummey’s River Thieves. Was it that one?”

Beothuk, pronounced Bee-oth-ick. Kind as she was (even giving us a printed list of a dozen Beothuk-related books), I couldn’t puzzle which one had made me aware of the tragic extinction of the “Red Indians” who once occupied the coastlines of Newfoundland.

In the jigsaw of my memory, I had only three pieces:

1. I read the haunting book in the seventies, 2. Newfoundland’s “Heart of Darkness”was a short paperback, and 3. The cover had a mystical design.

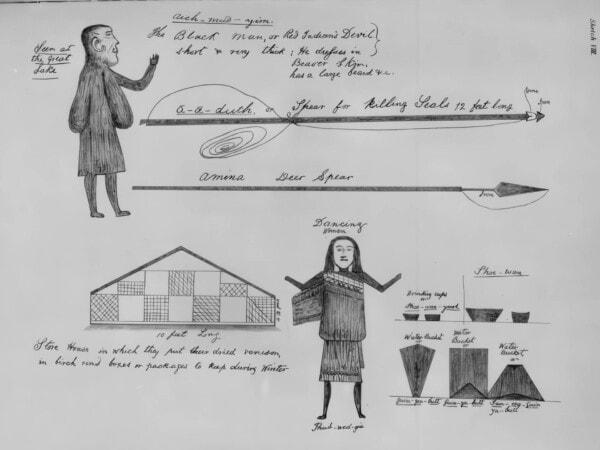

I recall the horrific suffering of the Beothuk—from massacres and starvation. That when their small group was attacked and their leader killed, his wife tore open her clothing and bared her breasts, hoping revealing herself as a woman that she would be spared. That the killer said he wished he’d shot a hundred, not just one. And that the last-known survivor was a woman (her name beginning with an “S”) who, for a brief time lived with her captors and left behind sketches reproduced in the book.

Thinking it may have been Riverrun by Peter Such, which our library doesn’t have, I ordered a second-hand copy online. Here’s how Peter prefaced his novel:

By 1800 the Beothuk population of Newfoundland had reached a critical point. Increased settlement had upset the delicate balance of their nomadic way of life and they were being indiscriminately slaughtered by the whites and their Micmac fur-trade allies, who were encroaching on Beothuk territory. Evidence suggests that about this time three or four hundred Beothuk were herded onto a point of land near their favourite sealing-site and shot down like deer.

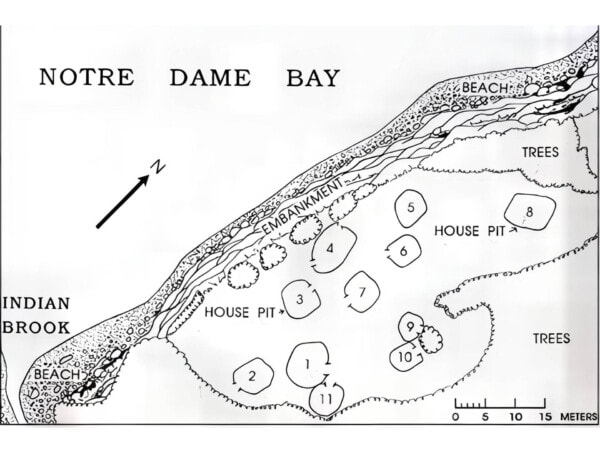

The Interpretation Centre is on the site of a three-hundred-year-old Beothuk encampment at Boyd’s Cove discovered in 1981. It’s at the end of Notre Dame Bay in northeastern Newfoundland, sheltered from the Atlantic winds and waves by a sprinkle of islands where seals, fish, seabirds, polar bears and caribou were in abundance three centuries ago.

As we wandered through the displays in the small interpretative centre, every now and then when she saw that something had caught our attention, the woman at the desk came over and gave us more details.

The colour red. That’s the first thing you notice in the dioramas, the film and the photos. The Beothuk mixed a red ochre with grease and used it to cover their skin and hair, decorate their shelters and birchbark canoes, and colour their tools.

We were surprised to learn that the Beothuk generally avoided contact with Europeans—they didn’t engage with fur traders or missionaries or Indian agents. They were referred to as a “population isolate” because they developed their unique culture in total isolation.

However, they did make “undercover” contact, stealing traps, plundering boats and robbing from the shore stations in the fall after the fishermen returned to Europe. (The Beothuk had great skill in reworking iron, suggesting early Norse contact and that they began living in the area around 1 A.D. At Boyd’s Cove, which they occupied from 1650-1720, more than 1,100 nails were found, most of them repurposed for weapons and tools.)

Why did they avoid direct contact?

The Beothuk could see that overhunting was leading to the declining health of the Micmac who were becoming more dependent on less-nutritious European food. And developing a craving for alcohol. And coming down with the “cough-demon.” Plus, fur trading meant spending the winter hunting small animals, that except for beaver, provided little or no edible meat: why leave the wigwam for that?

By the 1720s, Europeans had set up salmon nets six kilometres from Boyd’s Cove. A decade later, Twillingate was established thirty kilometres away. The Beothuk retreated inland.

In his novel River Thieves, Michael Crummey tells the story of Demasduit, the Beothuk woman whose husband was killed at Red Indian Lake. She was captured and lived with John Peyton and his family, dying a year later at the age of 23 in 1820 from tuberculosis. Three years later with most of her extended family dead from starvation or murder, her niece Shanawdithit, along with Shanawdithit’s mother and sister, were taken to St. John’s. The firsthand knowledge that we have about the Beothuk came from Demasduit and Shanawdithit.

When Shanawdithit, the last known Beothuk, died at the age of 28 in St. John’s on June 6, 1829, the Red Ochre People were declared extinct.

“You’ll see her statue on the trail to the archeological site. Right about here,” the woman who now felt like our personal guide said as she pointed out the location on the little map she showed us.

“What a great camping place,” we said to each other as we walked alongside the shadowed stream, the sun sparkling through newly unfurling leaves, shrubs flowering white, a clean pinesmell in the scrubby forest.

And there it was, off to the side of the path, the bronze statue of Shanawdithit, encircled by last year’s fallen leaves rustling in the wind.

Peter Such sets the beginning of his novel in 1818 with the words “This is where the riverrun ends.” The Beothuk had dwindled down to one band of only sixteen people, most of the women unable to conceive or carry a baby because everyone was so closely related. He ends Riverrun with this about Shanawdithit:

She died shortly after taking her leave of the explorer and scholar, William Cormack, who had harboured her for some months in his house at St. John’s and had questioned her extensively about her People…Her grave, originally in the Church of England cemetery on the Southside, St. John’s, was lost when the cemetery made way for a city street.

Was Riverrun the book that introduced me to the Beothuk? All I know is that reading (rereading?) it and visiting Boyd’s Cove coloured in the lines of the story of the Beothuk that is permanently camped in my memory.

Navigation

Beothuk Interpretation Centre. The walking trail is 1.5 km. There is also a Spirit Garden onsite.

Crummey, Michael. River Thieves. Toronto: Anchor Canada. 2002. A superb fictional account of what the Canadian Encyclopedia describes when “The governor of Newfoundland, although seeking to encourage trade and end hostilities between the Beothuk and the English, had approved an expedition led by captain David Buchan to recover a boat and other fishing gear which had been stolen by the Beothuk. A group from this expedition was led by John Peyton Jr. whose father John Peyton Sr. was a salmon fisherman known for his hostility towards the small tribe. On a raid, they killed Demasduit’s husband Nonosbawsut, then ran her down in the snow. She pleaded for her life, baring her breasts to show she was a nursing mother. They took Demasduit to Twillingate and Peyton earned a bounty on her. The baby died. Peyton was later appointed Justice of the Peace at Twillingate, Newfoundland.” In this book you learn that fur traders displayed chopped-off Beothuk hands as trophies!

Howley, James Patrick; and Cormack, William Eppes. The Beothucks or Red Indians: The Aboriginal Inhabitants of Newfoundland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1915. A 4 ½ pound book, the first comprehensive history of the Beothuk Indians of Newfoundland, which includes numerous illustrations and a reprinting of William Cormack’s journey across the island in 1822, as well as an analysis of the Beothuk language and several vocabularies and Shanawdithit’s famous drawings.

Pastore, Ralph. “The Boyd’s Cove Beothuk Site.” Heritage Canada: 1998-1999.

Stealing Mary: Last of the Red Indians is a documentary made about Demasduit who was given the name Mary.

Sparkes, Paul. “Lest we forget.” Saltwire. August 6, 2018.

Such, Peter. Riverrun. Toronto: Clarke Irwin, 1973.

Such, Peter. Vanished peoples: The Archaic Dorset & Beothuk people of Newfoundland. Vancouver: N.C. Press. 1978.

Winter, Keith. Shananditti. The last of the Beothucks. Vancouver: J.J. Douglas Ltd. 1975. A review of this book names the two notorious killers, “Rogers” and “Noel Boss.” “The latter apparently killed 99 Beothucks in his time and was known to express the wish that he could kill one more to even out his record. Rogers’ sad record was something over 60 of the people.”

2 Responses

This was a fascinating, albeit, tragic read! Your stories of Newfoundland, are drawing me there!

Thank you!

If the winters weren’t so fierce, I’d move to The Rock. We’ve even started watching (and enjoying) Son of a Critch!