Can you imagine what it was like for the first expedition team to summit Mount Mckinley (now called Denali), 110 years ago on June 7, 1913? Seeing the mountain every day during our stay at Camp Denali made us curious to find out.

Soaring to 20,130 feet, it’s the highest point in North America. The coldest mountain in the world and the farthest north, it “veils itself in weather of its own making,” its twin peaks barely two-hundred miles from the Arctic Circle. Summer temperatures plunge to -40°F, in winter they plummet to -75°F, a hellacious -118°F with the wind chill! Year-round, a storm rages two out of every three days. Climber Mark Horrell has reported, “It’s so cold I’m told you need to pee through a sock to prevent frostbite.”

Climbers of Denali have to scale 15,000 feet of snow and ice, three times that of the other “Seven Summits,” the highest mountain on each continent.

More than 35,000 people have attempted to summit Denali, but only 60% reach the top in any given year.

The first recorded attempt to climb McKinley was in 1902, a 105-day journey by Alfred Hulse Brooks and his team from the United States Geological Survey. Although the seven of them turned back at the base camp, it’s considered one of the grandest achievements of northern exploration.

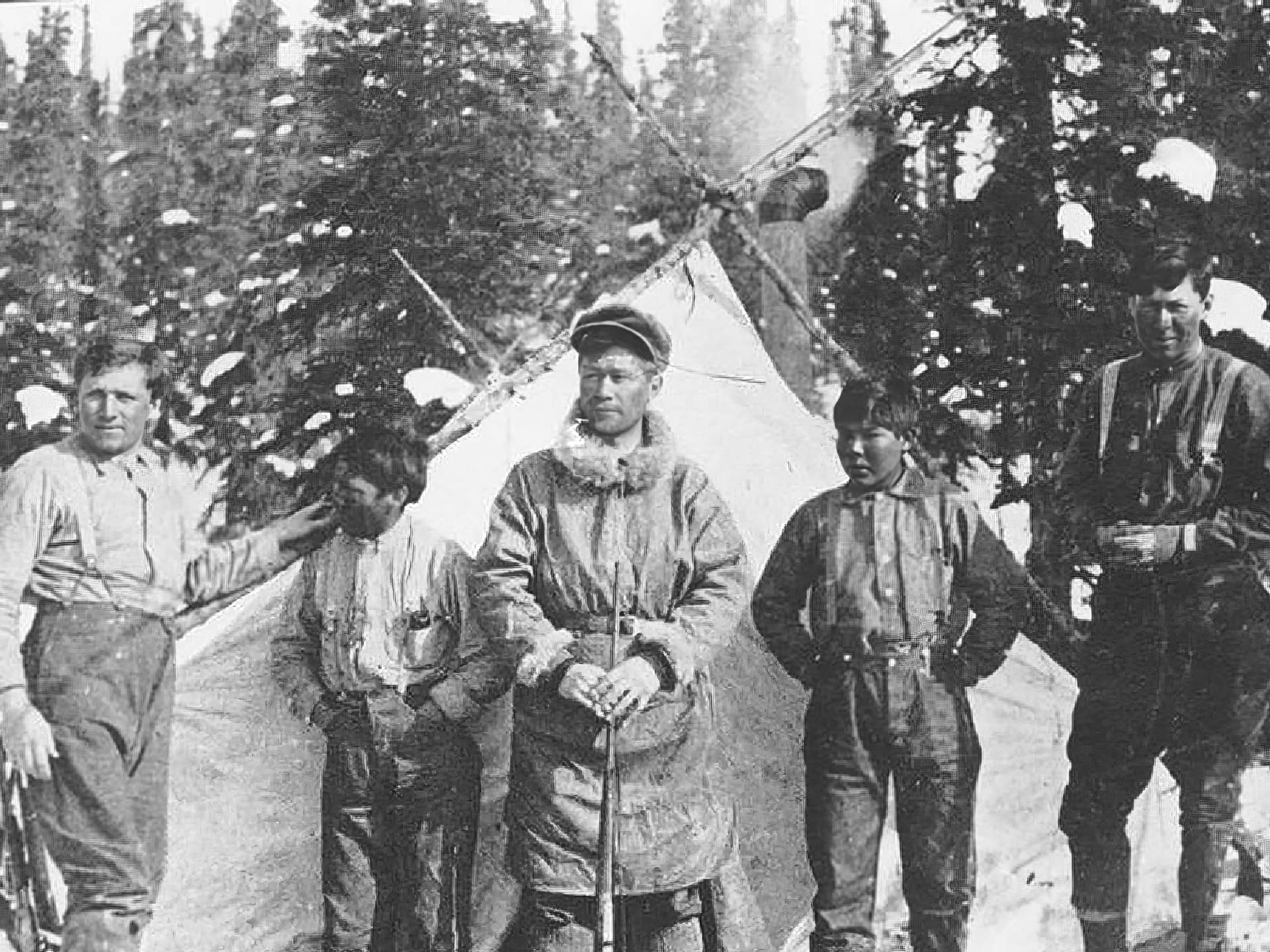

The first man to summit McKinley was Walter Harper. But credit for the success of the Stuck-Karstens expedition of 1913 rightfully belongs to Henry (Harry) P. Karstens, the second man to summit the peak of North America. It was Harry who rearranged the rope-up, putting twenty-year-old Walter in the lead so the honour of the first person to stand on the continent’s pinnacle went to a native Alaskan. Harry Karstens, you love him already, don’t you?

In 1895 at the age of 17, Harry left his Chicago home after a fight with his oldest brother. When he heard about the Klondike gold strike, he rushed to Dawson City.

When his luck there didn’t pan out (bad pun, sorry, had to do it) he ventured north to Alaska, to the Kantishina Hills—where Camp Denali is today—where nuggets of gold were said to be “the size of hen’s eggs.”

Harry wanted to climb McKinley. In 1906 and again in 1907, he worked with his friend, the naturalist Charles Sheldon, on expeditions to the base camp, assisting Charles in collecting specimens for national collections. In Wilderness of Denali, Charles wrote,

…I recall no better fortune than that which befell me when Harry Karstens was engaged as assistant packer. He is a tall, stalwart man, well poised, frank, and strictly honorable. One of the best dog drivers in the north and peculiarly fitted by youth and experience for explorations in little-known regions. He’s proved himself a splendid fellow, thoroughly efficient in all that pertains to practical life in the northern wilderness; inventive and resourceful.

The pair wanted to climb the mountain together. But Charles “spoiled it by getting married,” Harry is quoted as saying by Tom Walker, the author of several books about Alaska, including one exclusively about Harry, The Seventymile Kid.

Harry earned the nickname mushing a dog team to transport winter supplies and mail through the wild Seventy Mile River region—often travelling alone on a 250-mile route with loads weighing up to 700 pounds. He helped lay out the first incorporated city in Alaska and gained a reputation for indomitable dependability and incredible courage, strength and honesty.

Had Harry climbed McKinley with Charles, the expedition would likely have been more rewarding than it was with Archdeacon Hudson Stuck.

An Episcopal born on the outskirts of London in 1863, Hudson studied theology in Texas. Even Bishop Rowe, who turned over his quarter-million square-mile parish in Alaska to Hudson, called him “authoritarian, and a very difficult, temperamental, exasperating, somewhat egocentric man not always right and certain not always likeable.”

Hudson wanted to create a “God-fearing Christian Native people, living in a traditional way, free of white influence.” He fought for aboriginal land rights and local control of the salmon fishing and against teaching from standardized English textbooks. An energetic though frail climber, the preacher wanted to scale McKinley to draw attention and funding to the church’s work. He wanted Harry as his partner.

In the meantime, attempts to summit Mckinley continued by leaders with individual motives. Judge James Wickersham desired fame. Dr. Frederick Cook sought privilege and lied about reaching the summit. Miner Thomas Lloyd wanted bragging rights. Only Herschel C. Parker and Belmore Browne were true mountain men.

Harry didn’t want to climb with Hudson. But when bad weather and a shortage of supplies caused the Parker-Browne expedition of 1912 to turn back, two-hundred feet from the top, Hudson sprang into action.

The deal was that Hudson, nearly fifty years old by then, would finance the expedition and keep records—Harry’s role was to provide the critically needed mountaineering experience. Hudson said he “would never have attempted it without his (Harry’s) cooperation” and promised Harry a full share in the profits.

I’m guessing few others were rushing to join the preacher’s trek given the inexperience of the two climbers who did—they were barely out of their teens and had never tied into a rope!

Walter Harper was the robust son of one of the three “fathers of the Klondike” and his mother was a Koyukon Athabascan woman. Robert Tatum, a teacher at a mission school, had only been in the area for a year and had no mountain experience.

I marvel at the logistics that Harry arranged.

More than 2½ tons of gear to the base camp, hauled up by fourteen dogs, the teams managed by Esaias George and Johnny Fredson, both teenagers, only fifteen and sixteen years old. Esaias returned home with one dog team before the ice broke up. Johnny stayed and tended the other dog team at the Cache Creek base camp, “his loyalty and dedication during his month alone in the wilderness testified to his steadfast character,” writes Tom Walker.

And the food Harry organized.

Doughnuts!

Why doughnuts? Bread freezes too easily. Doughnuts are handy to carry in your pockets. And mixed with fruit and nuts, they pack a lot of calories. As Jack London wrote, “They are made much after the manner of their brethren in warmer climes, with the exception that they are cooked in bacon grease, the more grease, the better they are. Sugar is the cook’s chief stumbling-block; it is very scarce, why, add more grease.“

On the trail, the team made 200 baseball-sized orbs of boiled sheep and caribou mixed with rendered fat, marrow, butter, salt and pepper and pemmican, which they ate as their main meals, mixed with rice and erbswurst, a thick pea soup.

The expedition climbers set out on their arduous trip on St. Patrick’s Day.

Blocking their advance were two-storey house-size chunks of ice weighing hundreds of tons, upturned, fractured and jumbled by an earthquake the year before. The distance covered in two days by the Parker-Browne team took the Stuck-Karstens expedition three weeks.

A tent full of supplies and food burned, adding another three weeks to the trip while they waited for Walter and Robert to return from base camp with fresh supplies.

The day before the summit, the thermometer dropped to -21°F.

The four climbers took fifty gruelling days to reach the summit. But only two days to get down to base camp.

Most people relied on Hudson Stuck’s account of the expedition, which barely mentioned the conflict between the sourdough and the preacher that marred their grand achievement.

However, evidence of the acrimony was in Robert Tatum’s journal, the most personal account of the trip, which Tom Walker got a hold of from Harry’s great-grandson:

No work out of the deacon yet, continuing at sanctimonious whine when his bacon wasn’t cooked right his tea was wrong

(Hudson) was literally hauled up the last few feet before he collapsed unconscious on the floor of the little basin that forms the summit

an absolute Paresite (sic) and liar

That’s what you get for befriending a preacher

After summiting McKinley, Hudson’s reputation soared. He was made a Fellow of the Royal Geological Society and paid $28,000 for his story. A single speaking engagement at Carnegie Hall netted him $3,000. Some accounts say he made a total of $69,000 from the expedition, equivalent to $2,130,000 today.

Hudson gave Harry $1,150.

After the expedition, they never spoke again.

In the preacher’s defense, he did name Karstens Ridge in Harry’s honour. He titled his account using the name Denali not McKinley to honour the native word for the mountain. And some of his earnings did go to hospitals at Tanana and Fort Yukon.

It took Harry fifteen years to express what he really thought about Hudson: “He had entirely disgusted me with his untruthfulness from the time I first joined in the enterprise with him…Such is life for those who accomplish things but have no influence.”

The year after summiting McKinley, Harry married Louise Gaerisch, a nurse he’d met in Fairbanks between his trips delivering mail and supplies to remote camps in the Alaskan Interior. They had two sons.

In April 1921, Harry was appointed the first superintendent of the newly established McKinley National Park, a role for which he was paid the token sum of $10. He improved the roads, organized ranger patrols to reduce poaching and supervised the building of ranger cabins. He resigned the position in 1928. As Grant Pearson, a later park superintendent who also summited McKinley, wrote, “Perhaps the park was getting a little too tame for ‘The Kid.’” In 1946, climber Bradford Washburn named Karstens Col in Harry’s honour.

The first ascent of Denali was particularly challenging because the earthquake a year before shattered ice walls, destroying areas that were previously smooth and easy to traverse. The climb was made even more arduous by a surge of the Muldrow Glacier between 1906 and 1912.

The Muldrow Glacier is a 39-mile-long glacier that originates high on the northeastern slope of Denali and flows to the McKinley River. The last surge[s] of the Muldrow occurred [in 2021 and] in 1956-57, at which time the glacier advanced over 4 miles. Evidence of earlier surges, including one between 1906 and 1912, indicate that the Muldrow Glacier has a history of surging approximately every 50 years.

This section of glacier is normally easily and safely traversed and is the common northern route up Denali, but may be impossible to cross after a surge…

The Muldrow Glacier, which is usually slow moving and relatively smooth, suddenly appeared thoroughly fractured by cracks, called crevasses. The heavy crevassing extended throughout nearly the entire length of the glacier… A glacial surge is a short-lived, cyclical event where ice within a glacier advances suddenly and substantially, sometimes moving at speeds 10 to 100 times faster than normal.

NPS – Denali’s Muldrow Glacier

Here is a time-lapse of the surge between July 2 and August 23, 2021:

What a feat of mountaineering leadership on that first summit! We (and I suspect many others) were pleased to see Harry’s photo prominently displayed at the Denali Park Visitors’ Centre.

And happy to read a tribute in The American Alpine Journal to the true leader of the first successful climb of McKinley:

No one has been more intimately connected with Mount McKinley than Harry Karstens, who died November 28, 1955, in Fairbanks, Alaska. He lived the greater part of his life within sight of the mountain, and it was never far from his thoughts. He was the climbing leader of the first complete ascent of McKinley’s highest peak, the loftiest point in North America, and was the first superintendent of the National Park which was established to embrace that great mountain area with its abundance of wild life.

Navigation

Farguhart, Francis P. “HENRY P. KARSTENS, 1878-1955.” American Alpine Journal. 1956.

Heacox, Kim. Rhythm of the Wild. Connecticut: Rowman & Littlefield Guilford, 2015.

Pearson, Grant H., with Newill, Philip. My life of High Adventure. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1962. A park ranger at Denali for twenty-eight years and a friend to Camp Denali as you will have read in our Camp Denali #1, Grant also summited McKinley in 1932 and was on the climb with the Washburn’s.

Stuck, Hudson. “The Ascent of Denali.” New York: Charles Scribner & Sons, 1918.

Terrier, Stéphane. Climbing Denali, In Photos. NOLS Blog. Thanks Stéphane for giving us permission to use your excellent photos your 2017 expedition up Denali.

Walker, Tom. Denali Journal. Harrisburg, PA, US: Stackpole Books, 1992. A great storyteller—each book revealing the pioneering characters of Alaska.

Walker, Tom. Kantishna. Altona, Manitoba: Friesens Books, 2005. This book has an account of the Stuck-Karstens summit. The location of three trunks full of Harry Karstens’s journals, correspondence and gold nuggets from the Klondike was revealed to Ken Karstens, a great-grandson of Harry’s, by his great-grandmother on her deathbed.

Walker, Tom. The Seventymile Kid. Seattle: The Mountaineers Books, 2013.

4 Responses

enjoyed the story and the photos. another good one is the lost patrol out of Dawson City where a Northwest Mounties left never to return

Thanks for your feedback. In Sept 2019, after driving the Dempster Highway, we wrote about the Lost Patrol in our post Latitude 65: Within a Degree of History.

Thanks Barry; we feel the same way about these pioneering mountaineers and a greater understanding of those who turned back 200 feet from the summit. Think of the calories it would take, how many “meatballs” they each had to consume to carry on upward in the freezing, oxygen-deprived altitude. Yay Harry!

Awesome story and the photo’s fit right in with the story, remarkable people in a remarkable time.

Not an easy journey to be sure, considering the food of the time it’s remarkable they had the strength to get to the summit.

Happy Thanksgiving to everyone. 🍗🍗🍗🍗🍗